Blog by Mike Jones, Research Software Engineer in Research IT, University of Bristol

The purpose of this project was to explore the use of ‘Digital Humanities methodologies’ in analysing an English-language translation of a medieval Latin document. We used data analysis tools and techniques to extract financial data and entities (e.g. people, places and communities) from the translation. This process then enabled the creation of example visualisations, to better interpret and understand the data and prompt further research questions.

Primary source

The focus of the project was a single Irish Exchequer receipt roll from the latter years of King Edward I’s reign (1301–2). A receipt roll holds information on the day-to-day financial dealings of the Crown. It provides a rich source of material on not only the machinery of government but also the communities and people that, for various reasons, owed money to the king. An English-language calendar published in the late nineteenth century exists but was found to be deficient. A full English-language edition of the roll was edited by Prof Brendan Smith (Co-I, History) and Dr Paul Dryburgh (The National Archives) and published in the Handbook of Select Calendar of Sources for Medieval Ireland in the National Archives of the United Kingdom (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2005). The original document is in The National Archives (TNA), London, with the document reference E 101/233/16.

Transcript to tabular data

The starting point was the text published in the Handbook of Select Calendar of Sources for Medieval Ireland. A Python script was used to trawl the text, looking for details of interest, namely dates and payments, and add them to a CSV (tabular data) format. Using the Natural Language Toolkit we attempted to extract entities, such as people and places, using an out-of-the-box Parts of Speech (POS) tagger. The results were not perfect, with some places identified as people, but it was an encouraging starting point.

In the tabular data, each row recorded a payment, including the financial term, date, the geographic location or other entity they are categorised, the value owed to the Irish Exchequer. Payments, recorded in pounds, shillings, pence or marks, were converted to their value in pennies for more straightforward computation. We also checked our computed totals against those calculated by the medieval clerks of the Irish Exchequer – these were one penny out, the clerks having missed some fractions of a penny on 24 May 1302!

Data analysis and visualisations

With the data in a tabular format, it could be queried with the pandas data library, and visualised with the Matplotlib and Seaborn visualisation libraries. Querying the data, we were now able to create several visualisations, ranging from summary statistics for the financial year, drilling down to monthly, weekly and daily activity. We were also able to visualise the days the Exchequer sat, compared to days it did not sit due to holidays and feast days.

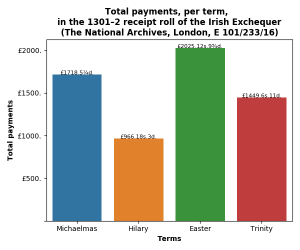

For example, the total value of the receipts for the financial year was £6159.18s.5d. In the following plot we can break-down the payments into the four financial terms: Michaelmas (September–December), Hilary (January–March), Easter (April–June) and Trinity (June–August), as shown in the chart.

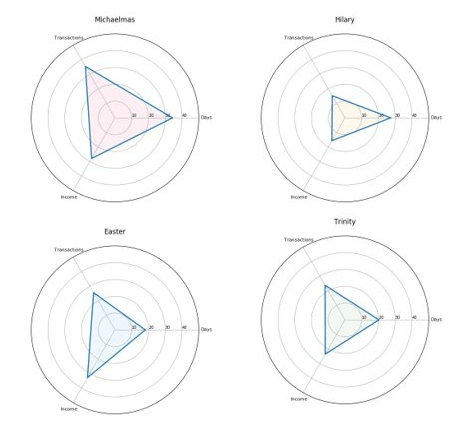

Other plots highlighted the variability of income, the amount of business (number of transactions), and the number of days the Irish Exchequer sat each term. This is illustrated in the following radar plots, where we plot all three variables – total revenue, length of the term and amount of business – with each variable represented as a percentage of the total value for the year.

What is immediately striking in these plots is that the Hilary term is relatively long but has the least business and income. In contrast, the Easter term is quite short but provides the most income. These plots confirm what the historians expected – the sheriffs made their proffers to the Exchequer in the Michaelmas and Easter terms and thus were anticipated to be busier.

Reception and response

While working on the project, findings and visualisations were shared on social media. This prompted interest and questions from other historians. For example, Dr Richard Cassidy asked (https://twitter.com/rjcassidy/status/1240944622186217472): ‘Was income concentrated in the first week or two of the Michaelmas and Easter terms, from the sheriffs’ adventus, as in the English receipt rolls from the 1250s and 60s?’ We were able to generate plots that showed in the Irish Exchequer the bulk of the income came in the fourth week and not the second.

Note: in the tenth week of Michaelmas, the spike in payments against a lower number of transactions is accounted for by Roger Bagot, sheriff of Limerick, returning £76.6s.8d. for the ‘debts of divers persons’; and £100 being returned by William de Cauntone, sheriff of Cork, in forfeited property of felons and fugitives.

Limitations and research questions

Clearly there are limits to the analysis, since the project only examined one financial year. It would thus be interesting to analyse trends over time. How does the 1301/2 financial year compare to others in Edward I’s reign? What trends can be seen over the years, decades and centuries? How was the income from Ireland affected by war, rebellion, famine and plague? Are there trends to be gleaned from the different administrations under varying chancellors? Also, does income reflect the changeable effectiveness of English royal authority in Ireland? Can we confirm the ‘decline of lordship’ narratives in the historiography of fourteenth and fifteenth century Ireland?

Future work

It is our intention to build on this initial work with the support of external funding. An application has already been made under the AHRC/IRC scheme ‘UK-Ireland Collaboration in the Digital Humanities’ to support a Network to investigate suitable DH approaches to the entire series of Irish receipt rolls, covering the years 1280-1420. Despite being unsuccessful, our application was highly rated and we intend to apply for a major research grant worth up to £1m under the same scheme when details are announced. Furthermore, we are committed to collaborating with Beyond 2022, an ambitious project to create a Virtual Record Treasury of Irish history. Beyond 2022 have commissioned the digitisation of a large number of documents held at The National Archives, London, including the Irish Exchequer receipt rolls. Plans include creating English-language translations of the Irish receipt rolls in TEI/XML, the de facto standard for encoding texts. It will then be possible to construct a pipeline, that builds upon this seed-corn funding work, that results in researchers exploring and formulating research questions around English colonial rule in Ireland and how the Irish interacted with English machinery of government.

Further Details

More detailed information about the project can be found in a series of blog posts, and the source code and data are available on GitHub

Jean Golding Institute Seed Corn Funding Scheme

The Jean Golding Institute run an annual seed corn funding scheme and have supported many interdisciplinary projects. Our next round of funding will be in Autumn 2020. Find out more about our Funding opportunities